by Margaret Smith, PhD Forage Agronomist

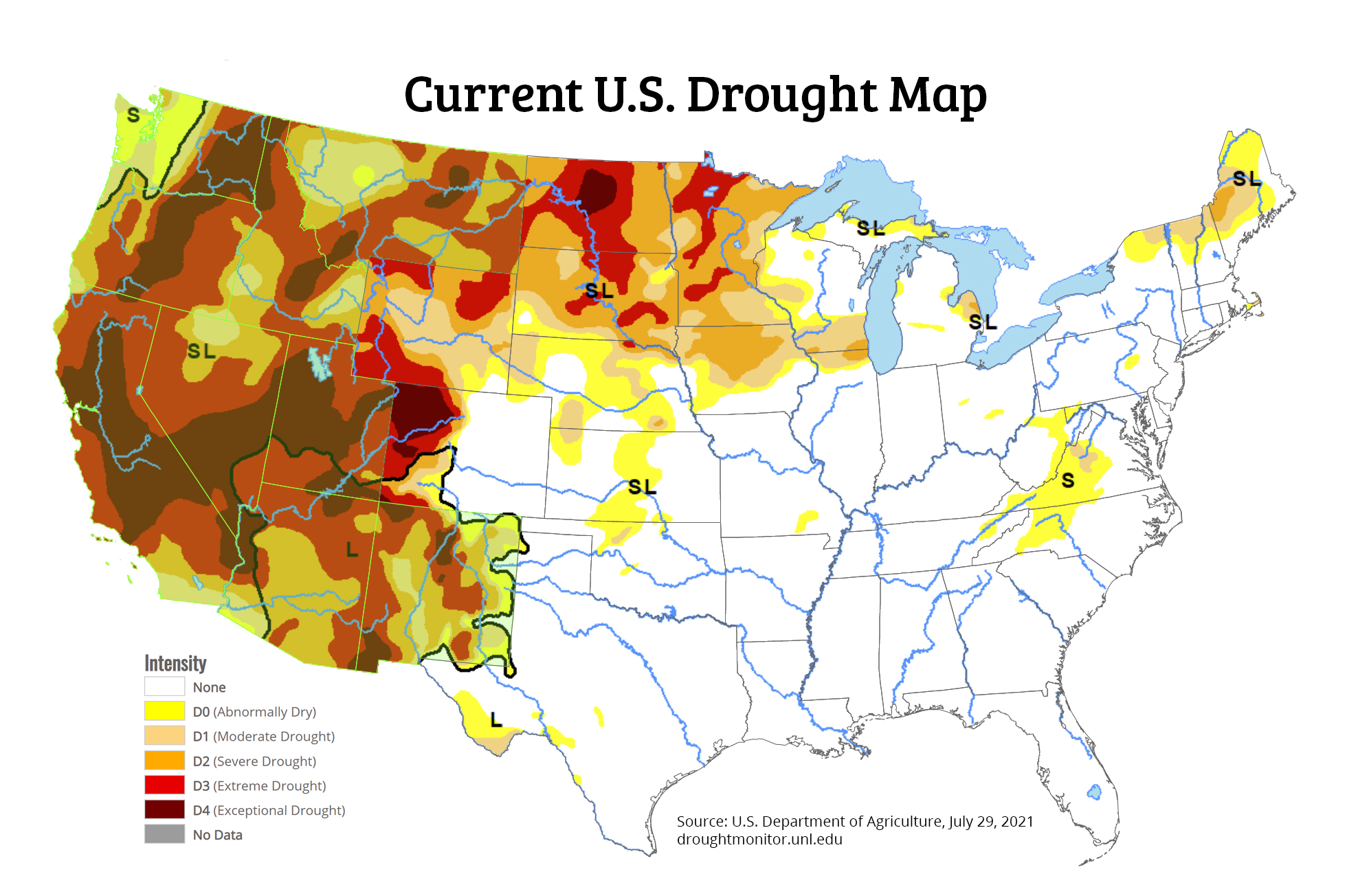

High nitrate levels in water-deficient forages are likely this late summer and fall in the drought-stressed parts of the Upper Midwest and west. In addition to the chance of nitrate accumulation in forages and corn slated for harvest, there is concern that some growers in the most severely affected parts of Minnesota and the Dakotas will be thinking about turning cows this fall into small grain fields, corn, and soybeans that don’t make it to grain harvest. These scenarios all present a potential danger to livestock—the most susceptible to nitrate toxicity being cattle (sheep are the least).

Thanks to the agronomists and animal scientists from the University of Minnesota and North Dakota State University, who have provided the following information about nitrates in forages and livestock poisoning during this drought year.

Key Points about Nitrate Accumulation in Plants

- Plants capable of accumulating high levels of nitrate include a wide range of crops and weedy species. Think corn and the forage sorghums, but many crops and weedy species can accumulate nitrate, including small grain regrowth, soybeans, millets, alfalfa, and several weedy species such as pigweed and amaranth.

- Drought-affected fields that were heavily fertilized with nitrogen or manure are more likely to accumulate nitrates than those with less added fertility.

- Nitrates primarily accumulate in the lower stems and leaves of corn, sorghums, small grains, grasses, and weeds. If you’ve suffered from drought this year, avoid harvesting the stalk or stem portions of your forage plant.

- Not all drought conditions cause high nitrate levels in plants. Some moisture must be available in the soil for the plant to take up nitrogen and accumulate nitrate. In plants that survive drought conditions, nitrates are often high for several days following the first rain (as the plant regrow following drought).

How to Manage High-Nitrate Forages/What to Do

- Consider ensiling your forages because it will allow conversion of nitrate to ammonia and can reduce nitrate levels by 30-50%.

- Haymaking does not reduce the nitrate level of the forage.

- Test suspected forages for nitrate levels before feeding them. Re-test suspected high-nitrate forages periodically due to variations that often occur in forages throughout a bag, bunker, silo, and after ensiling.

- Introduce suspected or high-nitrate forages gradually into the feed ration over 2-3 weeks to allow for adaptation.

- Feed another forage before feeding or grazing suspected or high-nitrate forage to help limit consumption of that feed.

- Limit dry matter intake per single meal if stored forage contains 1,100 ppm NO3-N (nitrate-nitrogen) or more on a dry matter basis.

- Mix high-nitrate forages (TMR mixer or tub grinder) to dilute the concentration in the overall feed ration.

- Observe animals closely for symptoms of toxicity (i.e., breathing, staggering, and signs of suffocation). Check the color of mucous membranes (eyes, mouth, etc.) two hours following the start of a meal consisting of a suspected or high nitrate forage (over 1,100 ppm NO3-N). Mucous membranes will turn from pink to grayish-brown at a methemoglobin content of 20% or higher in the earliest stages of toxicity.

- Call your vet IMMEDIATELY if you observe these symptoms in your livestock!

Further Reading

- Navigating Nitrate Toxicity in Feedstuffs, University of Minnesota

- Nitrate Poisoning of Livestock, North Dakota State University